Adapting Ptolus from 3e to Cypher System (CS) and 5e was a complicated task. There’s a lot of pure creative design work Bruce Cordell and I—developers of these two versions of Ptolus—did for all of the system-specific stuff in each version of Ptolus; we’d either convert existing material or create something from scratch to replace something that had become obsolete. If you haven’t already, check out the first part of this series, which more broadly covers many of the other conversions we did.

Compared to much of the other development and design work we did on the new versions of Ptolus, converting the Inverted Pyramid prestige class was a doozy. Prestige classes in 3e were special advanced classes your character could qualify for after achieving certain requirements (like a minimum amount of skill at stealth, or the ability to cast a certain level of arcane spells), and your base class didn’t matter (so a bard, sorcerer, and wizard could all qualify). The closest equivalents to that are 5e subclasses and Cypher System foci, but both of those work quite differently. The prestige class for the Inverted Pyramid (a secret guild of mages) had three class levels that worked like three separate prestige classes, allowing you to pick and choose which ones you wanted—an even weirder deviation from the normal prestige class rules.

For the 5e version, the biggest obstacle was making it work for sorcerers, wizards, and warlocks when all three of those classes work very differently and gain their subclass abilities at different character levels. I, as the version’s lead developer, ended up completely splitting it away from the class progression (one thing about doing game design is knowing when to follow the rules and when to break them to create something new). PCs can qualify by gaining access to 4th-level arcane spells and having an existing member sponsor their membership, with higher ranks achieved by paying dues, spending time in the organization, and getting approval from senior members.

The prestige class had three unique abilities: spell affinity (which lowers the spell level of one spell the mage knows), spell weaving (which lets the mage combine lower-level spell slots into a higher-level slot, or vice versa), and spell emphasis (which expends an additional spell slot to make a spell more powerful). 5e is more rigid about what a spell’s level is (compared to 3e where a spell might be 3rd level on the bard list but 2nd level on the wizard list), so instead of having spell affinity alter the chosen spell’s level, PCs regain a lower-level spell slot whenever you cast the chosen spell. Spell weaving stayed essentially the same as before, although because 5e mages have fewer spell slots at each spell level than 3e mages I reduced the number of spell slots you needed to combine to get a higher-level slot. Spell emphasis in 5e is conceptually identical to the 3e version, but also improves the spell’s attack bonus (which wasn’t a game mechanic in 3e). The description of these abilities also acknowledges that warlocks (who don’t have many spell slots) don’t get much out of fusing spells with spell weaving, but can still benefit from splitting a slot into multiple lower-level slots.

For the Cypher System, the version’s lead developer Bruce Cordell also did something unusual — he built Associates With the Inverted Pyramid like a focus, but you can’t take it until tier 2, its abilities add on to whatever ones you gain from your normal focus, and it only has abilities for three tiers (instead of six tiers like a normal focus). Of course, the Cypher System doesn’t use spell slots, so Bruce had to change the three Inverted Pyramid abilities to suit the new system. Spell Affinity reduces the Pool point cost of one ability (sort of like a special Edge that only applies to that ability). Spell Emphasis increases your Intellect Pool (this means you can cast more spells each day, which is conceptually similar to gaining more spell slots). Spell Weaving eases the use of the chosen spell (conceptually the same as the 3e version).

On average, Bruce and I each converted about ten to fifteen pages from the book per day. That included all of the basic formatting (like header notation, callout anchors, and so on) as well as actual game design (such as converting magic items and spells). Some parts, like most of the city district chapters, were fast; other parts, like the “Necropolis” and the “Adventures” chapters, took a lot longer because of all of the game stats, explanatory callouts, and references to other parts of the book that happen more frequently in room-by-room running text.

As we worked on these files, we had discussions with the rest of the team (mainly with Monte who acted as creative director, and with Shanna Germain and Teri Litorco, who shared the role of managing editor) about text styles for 3e, 5e, and Cypher System. For example, magic item and spell names in 5e appear italicized but do not in the Cypher System. Any time the text referred to a “potion of healing” or a “holy avenger” we had to italicize it in the 5e book but not in the CS book, which meant an entirely new notation in the files so our Art Director Bear Weiter could take care of it in layout.

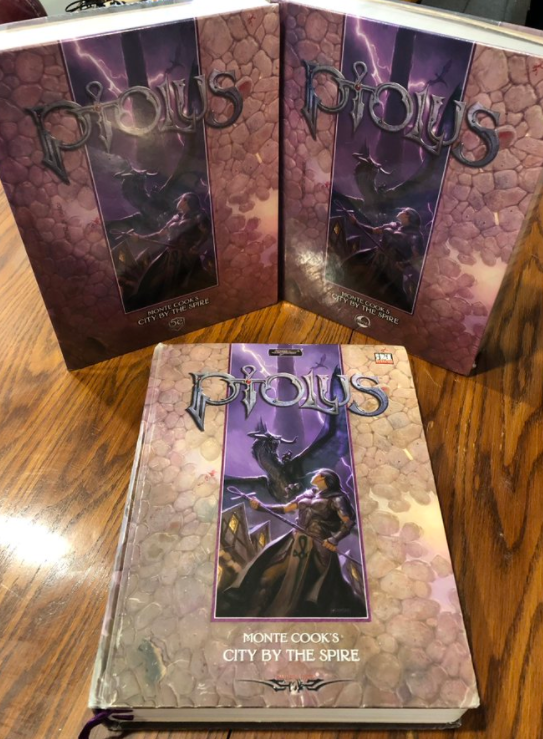

The manuscripts went off to production from our hands, where Bear laid out the book between Ray Vallese’s editing and proofing passes ahead of sending it to the printer. And now, three months later, I have a copy of each new version to go on my shelf next to my signed and numbered (5/1000) original 3e Ptolus.

Working on this book was … hard. It was also a lot of fun. It challenged us in unexpected ways. It definitely took a long time—longer than we expected. Monte warned us at the start that everything to do with Ptolus takes about twice as long as you think it will, and that turned out to be true. (Oh yeah, and in the middle of a global pandemic, to boot.) But it was definitely worth it.

So, what’s your next Ptolus character going to be? Let Sean and the rest of MCG know in the comments on or Twitter by tagging @seankreynolds and @montecookgames!