This is the sixth installment of New Gamemaster Month!

In New Gamemaster Month we’re helping players who feel the urge to run an RPG—to become a GM for the first time—take the plunge. Whether you’re new to gaming or a long-time player who’s never happened to take the GM’s seat, we’re making the process of running your first adventure an easy one. If you’re just joining us, start with the first installment. Then join us every Tuesday and Thursday throughout January, and by the end of the month, you’ll be a GM too!

We talked on Tuesday about encounters and their importance to the unfolding narrative of your game and the pace of play. Today we’re going to dress things up just a bit, by talking about the details that bring an encounter to life.

Details, Details

When I say “details,” I’m actually talking about three things: informational details, tangible details, and descriptive details.

Informational details include stats for creatures, maps of locations, details about the difficulty of a challenge, ideas for GM intrusions, and names, descriptions, and personalities of NPCs.

How much effort you put into these details is up to you. Not enough, and you’ll slow yourself down “winging it” as the encounter unfolds. And just like a missed retort, you may find yourself thinking an hour or a day later of what you wished you’d said at the time. On the other hand, too much detail wastes your time and energy, and often presupposes a particular manner in which the scene is intended to unfold—a manner that may not be the route your players take.

A well-designed encounter should at least have the following informational details:

- A map, if the lay of the land matters (this is most often the case in encounters likely to involve combat, and then usually when there’s something unusual or tactically interesting about the situation).

- The names of the important NPCs involved, and maybe some notes on their appearance, personality, attitude, and/or likely reaction to the characters.

- Game stats for any creatures or NPCs the characters are likely to go up against (in a fight or any other form of contest).

- The mechanisms and difficulties of any traps or environmental challenges present.

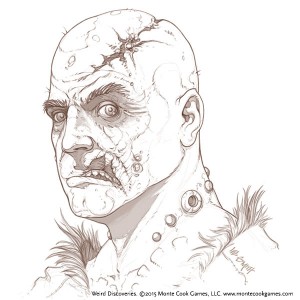

By tangible details, I mean things you can give or show the players. Sometimes an adventure will include illustrations specifically intended to show the players (a technique pioneered by the famous Tomb of Horrors adventure for D&D back in the day—we at MCG call them “show ‘em illos” when we include them our products such as Weird Discoveries). There may be maps the players can keep or props such as letters or other handouts. Even an illustration of a creature to be confronted can be handy. Your game doesn’t require this stuff by any means, but they can be useful and entertaining, and can sometimes save time (having a map they can refer to helps players understand the area with less confusion and without questioning you over and over, for example).

Finally, there are descriptive details, and this is where the art of GMing really shines. The informational and tangible details are largely a function of the adventure itself—in the case of The Beale of Boregal, for example, you get all the names and stats and NPC attitudes you need. And you’ll get some description, too, but what you do with it is what can make you a good—or even a great—GM. And that brings us to our activity for this session…

Step Six

You’ve already read The Beale of Boregal, but I’d like you to read some of it again. In particular, read through the Wandering Walk encounters, along with Encounters 1-6.

As you read, think about how you’ll portray locations and NPCs. Imagine them in your head; give them voice. Picture the scene: Is it dusk? What color is the sky? Is there a breeze at the Mouth Cairns Camp, and is that breeze warm or cool? What are the sounds and smells in Cylion Basin? Do children run underfoot? Can you smell cooking, or hear the crying of a baby from a local house?

Spend three or four minutes per encounter just imagining what it might be like. It’s OK to take some notes if you’re struck with a particular inspiration, but don’t overdo it, and here’s why: It’s very likely the encounter won’t play out exactly as you’re imagining, and you don’t want to overly commit yourself to a specific vision. But having something in your head—something with details and atmosphere—gives you the means to bring these encounters to life.

While we’re at it, read and bookmark these creatures:

- Broken Hound (page 232)

- Pallone (page 251)

- Scutimorph (page 257)

This time the purpose is two-fold: It’s good to have a look at the stats, to prep yourself with what the creatures’ capabilities and likely tactics are. But this reading also serves the purpose just mentioned. Think about the broken hounds—how will you describe them? Do they lurk in the shadows at first, or rush aggressively at the characters? Are there any sounds or smells or visual details that come to mind? Imagine them, so that when you unveil them to your players, you do so with color and excitement.

Feel free to share your imaginings on the New Gamemaster Month group on Facebook—you might find some inspiration there, too!

That’s it for this activity. Come back on Tuesday for the final week of New Gamemaster Month. You’re going to be running your first game soon—and it’s gonna be great!