In this series of articles, members of the team here at MCG look back at products we’ve released over the past decade and talk about their personal experiences in their creation, and the influence the titles have had on them as gamers, professionals, and just, well, people. It’s part of our celebration of Monte Cook Games’s first ten years. In this post, designer, company founder, and co-owner Shanna Germain talks about one of her favorites so far: We Are All Mad Here.

You can read other articles in this series here.

Content Warning: This post discusses depression and mental health issues.

These Black Dogs of Ours

Here are a few of my secrets that you can’t tell from my outside:

- I never know what I’m doing.

- I’m sure that every book or game I start will never be finished, will never be good enough, will not do what I want it to.

- Sometimes it is hard to get out of bed.

- Sometimes it is hard to get into bed.

- Sometimes the world is so dark and heavy it is hard to remember why a bed even matters.

The first time I read the term “black dog” as a metaphor for depression, I cried with despair and also with delight, because I wasn’t the only one, because I owned a black dog, because now I understood that I owned two black dogs—the one outside me that everyone loved and the one inside me that no one knew about.

Before that, no one had told me that I could look at my depression not just as a foe, but as a friend. A furry, loving friend who thought she was protecting me from bad things and didn’t understand her own weight when she pounced on my chest. A friend who was always with me (even in those moments when I told her to go away) because she was part of my pack. She was part of me, but not all of me. I gave my black dog a name that was meaningful to me, and taught her some simple tricks to keep her entertained, and when she wanted to come in from the cold, I learned how to open the door and let her in without her running roughshod over me.

Reframing my depression gave me a bit of autonomy, a sense of control, and as anyone living with a mental health issue knows, a feeling of control can be huge. For some, it can be life-changing and maybe even life-saving. Learning how to live with it constantly at my side has made me stronger and more empathetic to both myself and others, and has given me a deeper understanding of ways to move through a world built for neurotypical brains.

Many years later, when I sat down to write We Are All Mad Here, a game about fairy tales and mental health issues, I knew that it too needed a black dog. Not just as a metaphor for depression, but as a symbol of all the dark secrets we carry, the ones we’re born with, the ones that have happened to us, the ones that we have grown into and then out of—like plants in too-small pots. The ones we’ve adopted as our own.

Fairy tales are already stories of mental health issues, told in the guise of wolves and dark woods, of beheadings and betrayals, of being lost and alone without a path. But they are also stories of finding ways to live and thrive in the midst of those dark things. They remind us that there is also hope and promise—through tales of wild magic, of wishes granted, of our true selves seen and loved, of kindness imparted and promises kept. They show us how, even in our darkest hours, we may find joy and power in all the parts of ourselves.

Writing a game about the complexities of mental health issues through the lens of fairy tales was a risk on so many levels. Was mental illness something that people would even want at their game table? Could we honor all of the ways in which neurodivergent people live their lives, without ever crossing into the “broken” or “superpower” tropes? Would people balk at the idea that in this game, being neurodivergent was both a boon and a bane, a stumbling block and a strength? Could the game help people with neurotypical brains gain a deeper understanding and sense of empathy for those living with things like depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and ADHD?

I didn’t know the answer to any of these questions as I was designing the game. I just knew that it felt right to my own experiences. It felt true.

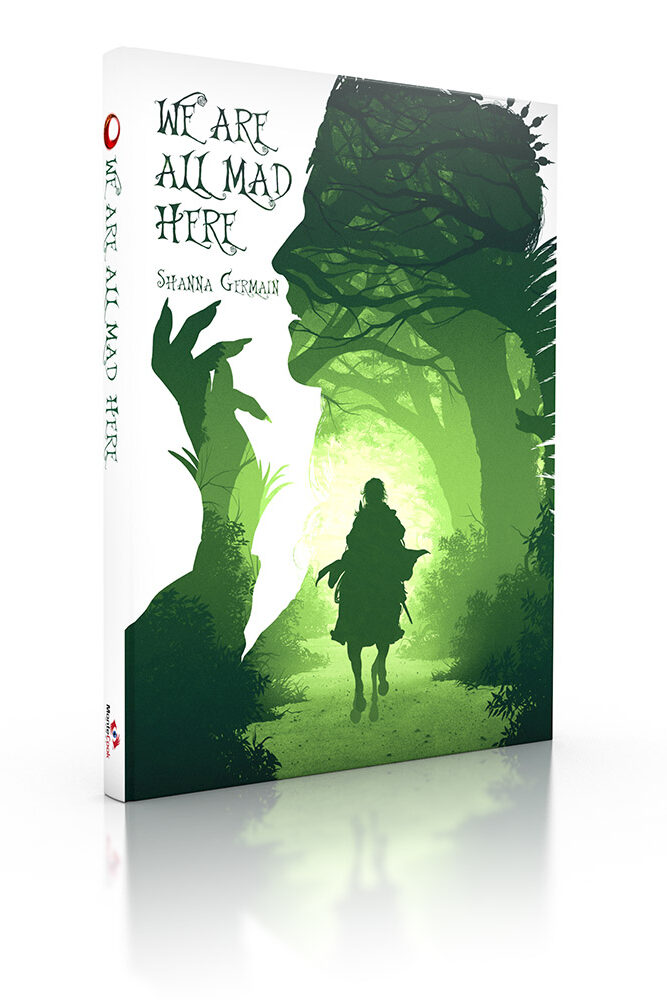

Just a sampling of some of the great art from We Are All Mad Here.

I’m proud of the games I’ve worked on in the ten years since we started MCG. I’ve put my heart into every single one of them, all while sitting in front of my laptop, with one black dog at my feet and another inside my brain. But We are All Mad Here stretched me in ways that felt at times deeply uncomfortable and also deeply meaningful.

It helped me understand that I don’t have to wrestle with my black dog all the time. Sometimes I can just let her sit beside me, her presence a familiar weight, her shadow a black comfort. And sometimes, at least inside the world of We are All Mad Here, where you can have a black dog as your literal companion, I can even let her aid me. She reminds me, too, that it’s important to rest, that it’s okay to ask for help, and that, even on our darkest paths in our darkest moments, none of us are ever truly alone.

From my black dogs to yours,

Shanna

We Are All Mad Here, by Shanna Germain, was released in September 2020. It’s a 224-page hardcover (or PDF) supplement and setting for the Cypher System. You can find it at the MCG Shop.